“A History of Magnolia Springs.” Excerpted from Evaluation for Historic Site Designation: Findings, Conclusion, and Recommendation (Magnolia Springs, Historic Resource 70-001). Memorandum from Thomas W. Gross to Prince George’s County Historic Preservation Commission. Upper Marlboro, MD: Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, July 11, 2017.

Statement of Significance

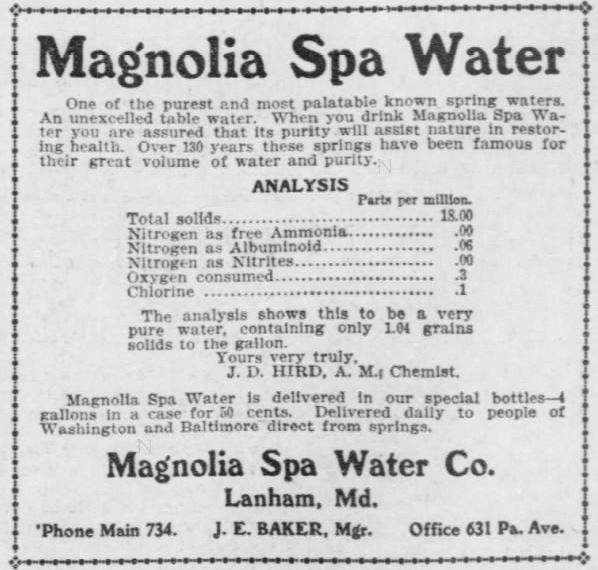

Magnolia Springs is significant as the location of a commercial water bottling facility that operated in the early twentieth century, a period in which such businesses proliferated in the Washington, D.C., area before the adoption of chlorination and filtration reduced concerns about municipal water supplies.

Historic Context

Magnolia Springs is located on property that was described in the County Land Records as early as 1865 as comprising parts of “Beall’s Farm,” “Addition to Bacon Hall,” and “Quebec.” The property was purchased in February 1903 by Enoch Baker Evans of Washington, D.C., who worked mostly in real estate investment and apartment building management but was also the first president of the Union Stock Yards Company, incorporated a few years prior.[2] Evans in May 1903 secured an approved plan of subdivision, which he called Princess Gardens, comprising 135 lots varying in size from one to seven acres; one larger lot, measuring 16 acres, encompassed the house site and the spring.[3] Evans owned the land at the time that advertisements for Magnolia Spa Water Company appeared in Washington, D.C., newspapers in 1906 and 1907. Several of the advertisements list the firm’s manager as J.E. Baker, who may have been a relative (Evans’ mother was born Elma Baker). The company’s address is given as 631 Pennsylvania Avenue N.W., the same building in which Evans maintained an office for his real estate business.[4] Evans and his family, including two servants, are listed in the 1910 census as living on Good Luck Road near the intersection with Lanham Road (Princess Garden Parkway).[5] It is not known whether the Evans family occupied the Beall-era house or a newer dwelling, nor could it be determined whether the house that appears in 1938 aerial photographs at that location was built by Beall, Evans, or another owner. A survey of drinking water sold in Washington, D.C., published in 1907 as part of a U.S. government report on typhoid fever, describes the extraction and bottling facility at Magnolia Springs. The survey states that the spring “is inclosed [sic] in a pipe of terra cotta and this is surrounded by masonry, which is roofed over by a wooden cover and closed by a wooden door.” Water from the spring was reportedly bottled by means of a funnel directly from the spring, passing through a cloth to remove foreign particles.[6] Evans and his wife sold the property in December 1910 to Harry Wardman and his wife, Lilian.[7] Wardman, a prominent real estate developer in Washington, D.C., was responsible for building over 700 rowhouses in the Columbia Heights neighborhood, 16 apartment buildings, and several luxury hotels including the Hay-Adams and what is now the St. Regis. Wardman’s intentions for the Lanham property are unclear, but he neither built on nor sold any portion of the land before selling it in 1912. Alfred M. Duckett, a Washington-based real estate investor and Prince George’s County native, owned the property until its sale at auction in 1916 to Mary Washington Keyser of Baltimore, a wealthy widow and collateral descendant of George Washington.[8] The property was next purchased in 1919 by Franz J. Coeln and his cousin Carola Kopf-Seitz, both recent immigrants from Germany.[9] A 1911 article in The Washington Post notes that Coeln, formerly a professor at the University of Bonn, had recently joined Catholic University as a professor of the New Testament; he would later serve as the school’s Dean of Sacred Sciences.[10],[11] Divine Savior Seminary Coeln and Kopf-Seitz sold the property in 1935 to the Society of the Divine Savior of St. Nazianz, Wisconsin, a Roman Catholic order established by German immigrants in 1854.[12] Topographical maps show that a seminary had been constructed on the site by 1944. The Society was forced to sell the property in 1969 to recoup financial losses sustained through its dealings with Victor Orsinger, a Washington, D.C.-based real estate investor who had been convicted a year earlier of stealing $1.5 million from the Sisters of the Divine Savior.[13] The order had planned to sell the seminary for about $2 million to be developed into high-rise apartment buildings, until a strong show of community support led to the creation of the Save Our Seminary (SOS) Committee.[14] The group raised funds to forestall the sale, including by selling tickets for a performance of the Ice Capades in January 1968.[15] Not only did this effort fail, the Society itself filed for bankruptcy in 1970.[16] Washington Bible College purchased the property in 1969 and operated a school and seminary on the site.[17] The property was most recently sold in 2017 to Washington Education Zone, LLC.[18] A church currently occupies several buildings on the site. Current Condition A 1967 article in The County News includes a photo of one of the original springhouses at Magnolia Springs, relatively intact and not far from a pipe from which water still appeared to be flowing. When the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission first documented the site in 1973, the springhouse still stood but was substantially deteriorated; the structure was no longer extant at the time of a 2008 survey. The most recent survey, conducted in 2015, found only scattered remnants of the springhouse, including brick and concrete blocks. The former spring site is now largely indistinguishable from its surroundings. [1] Land Records of Prince George’s County, Liber FS 2:496. [2] “Union Stock Yards,” The Times (Richmond, Va.), August 3, 1900. [3] Land Records of Prince George’s County, Plat Book BB 5:98. [4] “Magnolia Spa Water,” advertisement, Washington Herald, December 9, 1906. [5] 1910 U.S. Federal Census, Bladensburg, Prince George’s, Maryland, Series T624, Roll 567, Page 21B, Enumeration District 61, Image 107, Enoch Baker Evans. [6] Joseph Goldberger, “Sanitary Inspection of the Table Waters Vended in Washington, D.C.,” in M.J. Rosenau, L.L. Lumsden, and Joseph H, Kastle, Report on the Origins and Prevalence of Typhoid Fever in the District of Columbia, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1907, 161. [7] Land Records of Prince George’s County, Liber 69:19. [8] Albert Welles, The Pedigree and History of the Washington Family: Derived from Odin, the Founder of Scandinavia, B.C. 70, Involving a Period of Eighteen Centuries, and Including Fifty-Five Generations, Down to General George Washington, First President of the United States, New York: Society Library, 1879. [9] Land Records of Prince George’s County, Liber 138:468. [10] “Honor to Prelate,” Washington Post, October 13, 1911. [11] “Catholic U. Opens Term with Mass,” Washington Post, September 29, 1929. [12] Land Records of Prince George’s County, Liber 407:233. [13] “Find Attorney Took Nuns’ Building Fund,” Chicago Tribune, November 1, 1968. [14] “Neighbors Help Seminary to Stay in Operation,” Washington Post, May 21, 1967. [15] “Ice Capades Will Benefit Committee to Save Seminary,” Washington Post, August 20, 1967. [16] “Catholic Religious Order Files Bankruptcy Petition,” Washington Post, November 4, 1970. [17] Land Records of Prince George’s County, Liber 3735:725. [18] Land Records of Prince George’s County, Liber 40019:269.

Leave A Comment